HUNGARY

has been without a king since the Habsburg family was dispossessed in 1918.

But the country that never cared for the Habsburgs has suddenly turned loyal,

more loyal indeed than Austria, which had her emperors to thank for her wealth

and luxury.* Hungary still calls herself a kingdom and has constitutionally

remained one.

HUNGARY

has been without a king since the Habsburg family was dispossessed in 1918.

But the country that never cared for the Habsburgs has suddenly turned loyal,

more loyal indeed than Austria, which had her emperors to thank for her wealth

and luxury.* Hungary still calls herself a kingdom and has constitutionally

remained one.

(*During 400 years the Habsburg emperors of Austria were kings of Hungary as

well. Hungarian taxpayers could spend as much as they liked, or did not like,

on making the Royal Palace sumptuous. But the Habsburg kings preferred to reside

at the grim Hofburg of Vienna, where they were emperors and at home. The Hungarian

nation always remained foreign to them, and Hungary suffered greatly in consequence.)

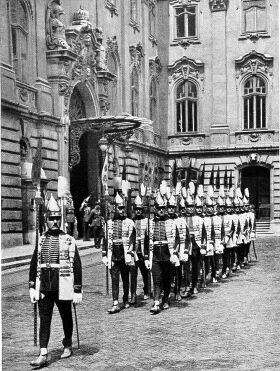

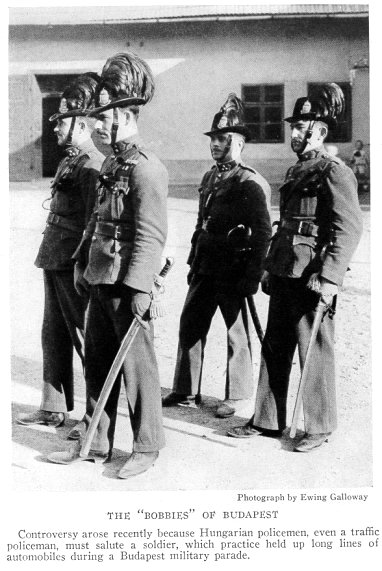

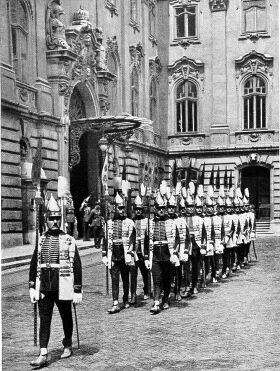

Admiral Horthy, who has been at the head of the Government for the past twelve

years, is styled Regent. He lives in the Royal Palace, but he has not discarded

the uniform of admiral of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, which has ceased to exist.

The Regent is acting temporarily in lieu of the king, though who that king may

be is yet to be seen.

THE NATION'S ULTIMATE RULER TO BI CHOSEN

King Charles IV, last Habsburg to be crowned Emperor of Austria and King of

Hungary, died ten years ago. The eldest of his eight children, Otto, is being

educated abroad, an exile from the countries his forefathers ruled, and brought

up in a way that he may take his place one day as king of Hungary, a country

that has been reduced by the Treaty of Trianon to one-third of its former size.

By another international agreement the Habsburgs are excluded from succession

to the Hungarian throne except under conditions most unlikely to take place.

So the question is in abeyance, and no one knows how long it may remain so.

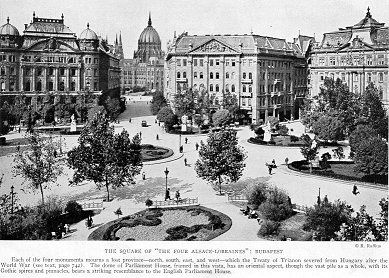

Thus has Hungary become that strange thing, unprecedented in history-a kingdom

without a king. Fortunately I forgot to think of all that whenever I looked

out of my window across the Danube. One can't keep up a climax of patriotic

depression for more than a decade and nothing would be further from the elasticity

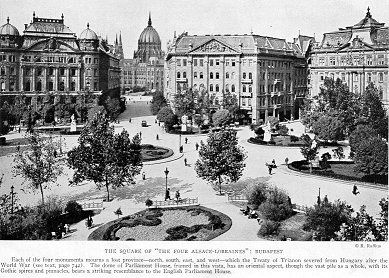

of the Hungarian character than to do so. I gazed upon the four bridges that

span the Danube to unite old Buda and young Pest-as a matter of fact, there

are six of them, but the two others are rather too distant to be in the picture-arid

reflected upon the best place to go and have supper.

THE CAPITAL'S SUMMER APPEAL

St. Margaret Island, gay with cafés and hotels, the gray ruins of the abbey

and nunnery where Princess Margaret lived and died, slumbering beneath the oaks,

glittered a green gem in midstream, with little white steamers and swift rowboats

scurrying around it. From the rear windows I could look out upon the roofs of

Pest, sweltering in the heat. No daring skyline to Pest- houses seldom rise

above five or six floors-and most of the honors of silhouette go to Buda's battlements,

outlined against the setting sun.

Beyond Pest, however, where the horizon meets the outskirts of the city which

houses a million  inhabitants,

beyond the long, straight line of Andrássy Street, lies green Town Park, waiting

for us with places of amusement, restaurants, and music. There are the pleasant

pavement cafés along the river, too, where one may eat ices and drink Tokay

wine and watch crowds sauntering past and lights glow, reflected in the slow-moving

river.

inhabitants,

beyond the long, straight line of Andrássy Street, lies green Town Park, waiting

for us with places of amusement, restaurants, and music. There are the pleasant

pavement cafés along the river, too, where one may eat ices and drink Tokay

wine and watch crowds sauntering past and lights glow, reflected in the slow-moving

river.

After passing in review all these summer joys of Budapest, we decided to stay

at home.

The children enjoyed it. They went marketing with cook, down below Francis

Joseph Bridge, to the Central Market Hall, where flat barges discard their loads

of fruit and vegetables at dawn, and mountains of melons and cabbages, of cucumbers,

and, above all, of paprika, Hungary's national spice, rise on the embankment.

They helped her carry home choice specimens of the screeching army of fattened

geese and juvenile chickens, to be bereft of their enormous livers or fried

in crisp bread crumbs and set afloat in paprika sauce, respectively, for the

benefit of the family.

The daily round of summer housekeeping in Hungary went on. Midday dinner remained

the feature of the day, a regular three-course meal, and preserves had to be

put up. Labor-saving in Hungary is as yet a dream. Of course, there are conserve

factories. The rich, mellow cherries, apricots, and peaches, with the glow that

the dry, warm climate and the volcanic soil lend to Hungarian fruit, stand in

canned rows on grocers' shelves here, as elsewhere, to be had for the asking;

but few really selfrespecting Hungarian housewives do ask for them.

When

we had finished the apricot jam and the candied strawberries, there came a clay

when the cook, the housemaid, and I wallowed in tomato sauce. Then two bricklayers

sprawled upon the bathroom floor, since summer is the time for repairs,

When

we had finished the apricot jam and the candied strawberries, there came a clay

when the cook, the housemaid, and I wallowed in tomato sauce. Then two bricklayers

sprawled upon the bathroom floor, since summer is the time for repairs,

and a youth undertook to paint the bedroom ceiling, pacing the room, huge as

a primeval giant, using his ladders for stilts and whistling melancholy tunes

from morning till night. Thereupon I sat down and declared I was through.

"Very well," the head of the family acquiesced. "But you are

not to start over again, tiring yourself out with getting clothes and shutting

up the apartment and that sort of thing. We will spend a fortnight with the

Sághys at their Balaton estate; they have asked us ever so often. We don't need

clothes there. And as soon as they have a new batch of visitors coming in, we'll

just take tó our heels and roam about the country for a bit. The Carpathians

might be cooler, but `see Hungary first' is not a bad slogan."

THE FIRST BUDAPEST BRIDGE NEARLY A CENTURY OLD

The night before we started a lovely thunderstorm broke over Budapest. A fierce

deluge of almost tropical rain washed the trees, the hills, the houses, to a

gemlike morning brilliance.

The car that was to take us to our destination sped across Chain Bridge, the

first that had joined Buda to Pest a little less than a hundred years ago, taking

the place of the old boat bridge that used to be put up every summer. Count

Stephen Széchenyi was one of those great dreamers of Hungarian dreams whose

career ended in tragic defeat, but he had realized some of his great conceptions,

at least : the Chain Bridge, Danube regulation, and the Academy of Science,

in front of which stands his statue.

Our son István is young enough to shudder every time we pass below the St.

Gellért  Memorial

upon the cliffs (see page 742), supposedly on the very spot from which the martyr

bishop, who first tried to convert stiff-necked pagan Magyars to Christendom,

was rolled down in a barrel into the angry river.

Memorial

upon the cliffs (see page 742), supposedly on the very spot from which the martyr

bishop, who first tried to convert stiff-necked pagan Magyars to Christendom,

was rolled down in a barrel into the angry river.

Soon the fates of bishops and martyrs were forgotten in the delights of "real

country." One can drive miles and miles

and miles in Hungary without seeing a trace of human habitations. Even in the

districts west of the Danube, which are by far the most densely inhabited, villages

and houses are few and far between. There is no waste land, however, in this

part of the country.

The storm of the previous night had done away with the white dust that is the

curse of the highways of Hungary, and the splendid Budapest-Balaton road stretched

out invitingly before us. We sped along the pleasant countryside, through the

occasional peaceful little one-horse towns and villages, consisting mostly of

a single wide main street, no more than a double row of low whitewashed cottages.

Two windows and a wide yard-gate face the street on each house and pillared

porches run along the whole length of the house on the yard side.

FOOTBALL AND HORSEBACK RIDING MOST

POPULAR SPORTS

At Székesfehérvár our older boy, János, tried to rattle off all that he had

learned about this ancient city, where kings of Hungary were crowned, down to

Ferdinand the First. Fortunately, however, we were passing the city playgrounds

and a football match that was in progress claimed the wayward attention of my

sons.

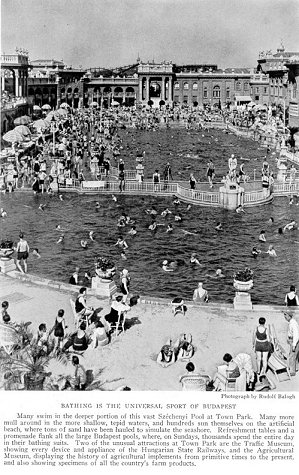

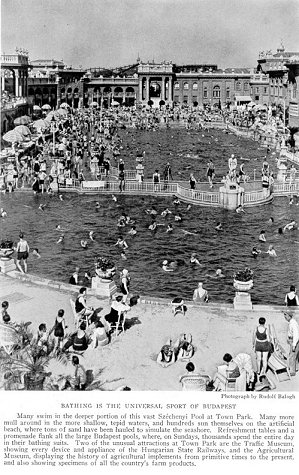

Football

has become almost a national game in Hungary. Baseball and basketball are unknown,

but Olympic and other international prizes speak for Hungarian prowess in football,

fencing, and swimming. Horseback riding is another national sport, tennis is

very popular, and athletics, which until recently had no part in any school

curriculum, now play a very large part indeed. A State college for physical

education has been established, and most boys under twenty - one are either

scouts or "leventes"- a term perhaps Nest translated by the words

"young knights."

Football

has become almost a national game in Hungary. Baseball and basketball are unknown,

but Olympic and other international prizes speak for Hungarian prowess in football,

fencing, and swimming. Horseback riding is another national sport, tennis is

very popular, and athletics, which until recently had no part in any school

curriculum, now play a very large part indeed. A State college for physical

education has been established, and most boys under twenty - one are either

scouts or "leventes"- a term perhaps Nest translated by the words

"young knights."

Practically every village boy is a "levente," but the term signifies

little save that the youths are drilled in their spare time in moral and physical

discipline.

LAKE BALATON IS HUNGARY'S OCEAN

The first glimpse of Lake Balaton, the "Hungarian Ocean," comes at

I,epsény, but nobody looks at it. The road here runs across an estate belonging

to the Nádasdy family, one of the most ancient and aristocratic of the country.

Countess Nádasdy had the idea of establishing a charming little roadhouse for

motorists at Lepsény, where excellent food and the choicest of Hungary's famous

wines are served by lackeys in knee-breeches. The Countess remains in the background,

but supervises her business, and no Budapest storekeeper running clown to Balaton

to spend a weekend with his family can resist the temptation of stopping here

to partake of a meal prepared by an aristocratic chef.

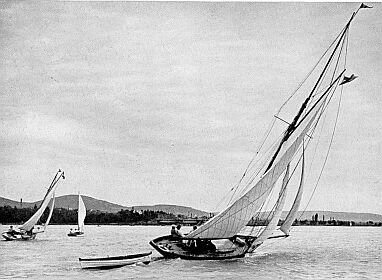

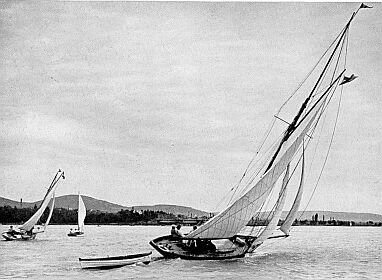

Soon Balaton spread before us, wide and calm. It is the largest lake in central

Europe and one of tile least known. It has the atmosphere and the moods of the

sea the loneliness, the colors, the whims, the untamed self-will of the ocean.

Storms come with terrific suddenness, and only old lakedwellers, boatmen, and

fishermen can read their signs (see, also, page 6c~4).

The stunner vacationists who flood the little lakeside places during July and

August often do not believe these old oracles of Balaton, who can discern, even

on a calm sunny day, the glassy green color of the water that forebodes evil.

Fatal disasters to canoes and yachts claim their victims every summer.

LIFE ON A HUNGARIAN ESTATIE IS FEUDAL

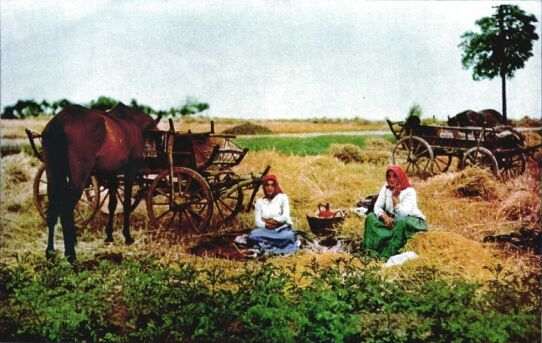

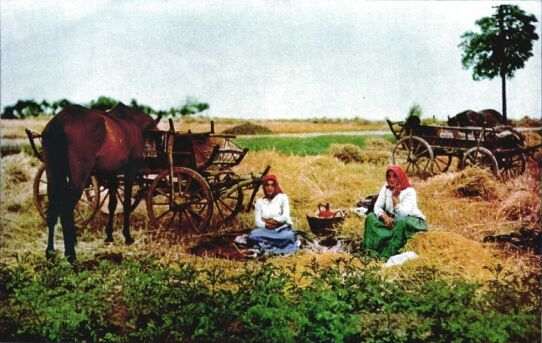

Balatondombori is a puszta of a thousand acres. Puszta is a term with a double

meaning. It signifies an estate or farm and at the same time it means the barren

plain, best translated with the Russian term of "steppe." There is

nothing barren about Dombori, however. Wheat, corn, rye, beets, flax, even lentils,

and other vegetables are grown on the puszta, and some of the finest cattle

in Europe graze in its meadows. The fields are bordered by apple, walnut, and

mulberry trees, and you eau never be sure when a little boy, his skirtlike linen

trousers stained with mulberry, his mouth likewise, will drop upon you from

a wayside tree, where he has been picking leaves for the silkworms, which the

peasants of this section tend in great numbers. Fences are practically unknown

in Hungary, except for lattices and plaited twigs around yards and gardens.

Life on a Hungarian estate is feudal and patriarchal at the same time. Our

destination, the pleasant country house at Dombori to which the peasants on

the farm and in the tiny adjoining village had given the grand name of "the

castle," was a groundfloor, whitewashed building of nine rooms, larger

but not much more imposing than the letter type of peasant cottages in the village.

It had all the difference of modern improvements, though, whereas the Hungarian

peasant aims at improvements only as far as his agricultural work goes.

Bathrooms are an unknown quantity in a peasant cottage, and the Nest room,

the "clean room," as it is called, is not lived in, bat kept merely

for show. A bed is piled as high as the ceiling with down-filled, elaborately

embroidered pillows and eiderdowns, but no one sleeps in it. The kitchen, the

porch, and perhaps another room suffice for the needs of the family.

THE IDEAL GUEST IS OBLIGATED TO GET FAT

In the peasant farmer's barn, however, you play find the most modern agricultural

machinery he can afford, and though Mr. Farmer has no knowledge of literature

or the fine arts, he is steeped in the sane philosophy of the man of the soil,

and has a profound interest in and mostly a very shrewd view of politics and

the wheat market. The Hungarian peasant talks little but he talks sense.

The "castle" at Dombori, however, is a home of culture and an ideal

place for being delightfully lazy. The only drawback to a Hungarian estate is

that you must get irrevocably fat. All the swimming in Balaton was of no avail

against the detrimental effects of the cuisine of the puszta. "Pörkölt"

chicken, turós csusza (dough boiled and garnished with cottage cheese, cream

and greaves), stuffed cabbage, and, above all, the royal dish of paprika fish

- richly seasoned stew that contains all the choice produce of the lake, which

prides itself on the variety of its finny tribes - cannot be withstood, especially

when you are a guest and don't have to look after the cooking.

Our hostess spent the hot mornings in the kitchen ordering about her scullions,

while we acquired appetites for dinner in the cool lake. I doubt, however, whether

we derived more enjoyment out of our kind of sport than she did out of hers.

She is a Hungarian housewife of the old school and is never happy unless she

has the house full of guests.

It is the head of the family who invites the guests, who is deeply hurt and

offended when they go away, who used to have carriage wheels removed just to

keep his guests there longer, in the good old clays when guests came in carriages,

and he blames his wife if visitors leave before they have gained at least five

pounds-a standard which must be kept up for the honor of the house and of which

a record is kept in the Dombori guest book!

THE "COW-UNCLE'S" FOLK TALES

Pali

bácsi, the "cow-uncle" (small children always call older people "aunt"

and "uncle" in Hungary), was a great friend of my boys. Of the many

folk tales he related to them none were more popular than those legends relating

to the castle ruins that crown the volcanic basalt hills along the north shore

of the lake, and the tale about the peculiarly shaped pebbles - "goats'

nails" - that are found on Tihany Peninsula.

Pali

bácsi, the "cow-uncle" (small children always call older people "aunt"

and "uncle" in Hungary), was a great friend of my boys. Of the many

folk tales he related to them none were more popular than those legends relating

to the castle ruins that crown the volcanic basalt hills along the north shore

of the lake, and the tale about the peculiarly shaped pebbles - "goats'

nails" - that are found on Tihany Peninsula.

The story goes that in ancient times a beautiful golden-haired princess (Who

ever heard of a dark princess?) tended her golden-fleeced goats on Tihany Hill.

She had a lovely voice and was so proud of it that she guarded it jealously

from all people, thinking no one was good enough to hear it. The son of the

King of Balaton chanced to hear her one day and forthwith fell so deeply in

love with her voice that he sickened with longing to hear it again.

The princess tossed her head and refused to sing for him, although the youth

spent his days sitting on top of a wave just to catch a glimpse of her, and

ultimately died of longing. Thereupon irate King Balaton stirred up a storm

in which all the goldenfleeced goats were drowned. The lake still flings up

their nails on Tihany Beach when it is stormy.

As for the princess, she was imprisoned in a cave on Tihany Hill, and the penalty

for her pride is that she must now answer anyone who cares to call to her. This

is the origin of the famous Tihany echo. When T was a child the Princess repeated

twelve or thirteen syllables, but so many villas have since been built on Tihany

that soon nothing will remain of the echo but the legend, and the Princess will

be well out of it.

As a worthy conclusion to our Balaton visit, we took the children on a motorboat

trip around the lake, visiting the twenty - odd small resorts and the few larger

places - Balatonföldvár, patronized by the wealthy; Siófok, summer paradise

of Budapest tradesmen's families ; Balatonfüred, health resort whose hot springs,

baths, and sanatorium are visited at all seasons of the year.

Balaton is a wonderful place in winter. The enormous frozen expanse, with its

famous sunsets, is incomparably beautiful, but the dwellers of the few lakeside

townships - Keszthely, Tapolcza - keep the pleasures of ice sailing, ice tobogganing,

and winter fishing through holes cut in the ice for themselves. Only Balatonfüred

has winter comforts for visitors.

THE LAST HABSBURG OCCUPIED A CELL IN TIHANY ABBEY

A kindly Benedictine monk showed us over Tihany Abbey, from the vault in which

lies interred King Andreas I of Hungary to the small bare cells where the last

king, Charles, and Zita, his wife, were interned in 1921.

Charles, landing in a plane that brought him from his exile in Switzerland,

had made one last attempt to regain his throne. He failed and was escorted by

water, across Balaton and along the Sió Canal, to the British cruiser Glowworm,

which took him down the Danube, by way of the Black Sea and the Dardanelles,

to Funchal, in the Madeira Islands, where he died a few months later.

Since we had contrived to gain twenty pounds among us in a fortnight, there

was no offense in saying farewell to our hosts, and the "castle" at

Dombori was ready to receive the next batch of visitors to be nourished.

BAKONY FOREST HARBORED ITS ROBIN HOODS

We motored through Balcony Forest, a region that still teems with legends about

19th - century highwaymen. "Poor fellows," the peasants called these

romantic figures, who were sons of local families, and the population, though

fearing them, had much sympathy with their exploits.

Our chauffeur, who had been evolved from a Balcony coachman, had learned the

ins and outs of a motor, but his heart was still attached to horses. His eyes

sparkled when he spoke of the horse-stealing feats of Sobri Jóska, the famous

Balcony highwayman.

"This is just where Sobri Jóska shot down, single-handed, the four gendarmes

who had brought three of his men to the gallows, and he got away with all the

four horses, too," he added with enthusiasm.

Twilight was falling and I caught István glancing apprehensively round his

shoulder once or twice, although János jeered, "Silly ; that happened eighty

years ago !" But none of us minded getting out of the gloomy forest.

We spent the night at Veszprém, and in the morning at Körmend viewed a princely

mansion on one of the feudal domains of the wealthy old landed aristocracy of

Hungary.

We motored into Szombathely, a busy commercial center, and to the lovely old

Romanesque church at Ják. This is one of the few churches that were spared during

the Tatar invasion in the 13th century and by the Turks also. The Ják church

is beautifully restored and well worth seeing. But after Ják István rebelled.

He would have none of the fascinating Renaissance and baroque buildings in Sopron,

one of Hungary's most cultured provincial cities. He wanted his dinner and a

swim in Fertö Lake. But when he saw the reed-grown banks and the gray, dense,

shallow water of the lake that is now the boundary between Hungary and Austria,

he made a f ace.

"Balaton water is quite, quite different," he declared. "even

the Danube is more blue. Why, one can't swim in that-just wade." In rainless

summers it dries up entirely.

Austria, being better versed in salesmanship than Hungary, is nevertheless

making much of her side of Fertö. The reeds have been cleaned out, restaurants

and huts for week-end camping built on poles right into the lake, and trains

and motor buses convey

many visitors from Vienna. But my son was right. We got stuck as soon as we

started to swim, and even a sail in one of the shallow canoes failed to pacify

him. But my mother's heart saw advantages in a lake where drowning was out of

the question, although foundering seemed probable.

BACK IN BUDAPEST

In the afternoon we returned to Budapest by way of Gyor. Komárom, and Esztergom,

the seat of Hungary's highest church dignitary, the Arch Primate. The beautiful

cathedral on top of the hill overlooks the Danube, far into the country that

is now Czechoslovakia. An hour later we were back in our apartment.

The lights on the Danube, the radiance of reflectors shed on the Bastion and

the Citadel, looked as lovely as ever, but the apartment reeked of camphor,

naphthaline, paint, and plum jam. The flowers in the window-boxes looked parched,

and I realized I had missed my chance of winning a prize at the municipal competition

of "Flourishing Budapest" in the fall.

If you speak to a Hungarian he is sure to tell you during the first five minutes

of the conversation that there is no nation as unhappy as his own. A tragic

war, a disastrous peace, economic troubles, and unsolved political problems

might be expected to cast a shadow over this lighthearted city; but the casual

observer can not discover it. We have evidently grown used to troubles and carry

them well. Whenever you go to a restaurant or a play in the company of a Hungarian,

he will invariably wonder how all those people can afford to be there, and he

forgets that he is one of those who can't.

A DETOUR TO MEZOKÖVESD, FAMOUS FOR EMBROIDERIES

On the whole, I didn't mind leaving Budapest again on the following Sunday.

We had an excellent excuse for doing so. Our cook's sister was about to be married

and had invited me and the boys to the ceremony. Their home is in a slightly

out-of-the-way place-only two hours' walk from Eger, the nearest railway station.

Not a two hours' drive-the road isn't fit for that. A tiny village in the Mátra,

the highest range that is now left to Hungary.

That gave our trip somewhat the character of an excursion. The boys insisted

on taking a picnic lunch with us, although I told them, knowing what a wedding

feast means, that they would have all the trouble of carrying it home again

in their rucksacks. Incidentally, as it developed, there was no need to get

lunch or dinner for two days after. We were saturated.

I thought we might as well make a detour to Mezokövesd, the village of famous

costumes and embroideries, beloved by tourists. We started at an unearthly hour,

to be in time for early mass. I told the boys all about the gorgeous pageant

of beautifulpeasant costumes that they were going to see-the girls in white,

with intricately worked embroidery on countless petticoats, on finely bleated

blouse sleeves, on kerchiefs and shawls, with glittering, bespangled headdresses.

The women would wear shawls over their heads; they have no right to wear the

párta, or headdress, after they are married. "To tie up a girl's head"

is another way of saying "to marry her," and "a girl who has

kept on her párta" is a polite description of an old maid.

I told them the young matrons would be as gay as peacocks in their embroidered

aprons and skirts with bright ribbons, and the men would be resplendent in the

apparel that is characteristic of this part of the country-richly worked aprons

down to the ankles, full embroidered shirt sleeves,

gay cravats and streamers to their hats.

The embroidery techniques and patterns come down from mother to daughter and

belong exclusively to the various villages, like the patterns of Scotch tartans

belong to a clan.

Export trade discovered Mezokövesd embroidery some years ago. Since that discovery,

the patterns sometimes even come down from mother to son, for the lads are not

ashamed to ply the needle in winter, when there is no work in the fields.

We drove into Mezokövesd at a high pitch of excitement, only to find the market

place in front of the church deserted. A few old women in their peaked black

shawls were straggling about, a few children dressed like miniatures of their

elders, but no trace of the customary "church parade." Mass was over

; the ceremony evidently seemed to have been quickly disposed of.

István struck up a lightning friendship with a youngster who was munching mulberries

on top of a fence, and while we were yet helplessly wandering about in quest

of a bespangled párta or a few dozen swishing petticoats, he got information

and mulberries out of his new friend.

"It's market day in the next village, the big annual fair," he called

out. "That is where everybody has gone ; Feri here only stayed behind to

take care of his granny, who's sick !"

A PEASANT WEDDING

But the wedding was a distinct success. I have wandered about a good deal in

my country, but I had never seen this type of festivity before. Juliska, our

cook's sister and our housemaid of the previous year, was not as beautifully

attired as the Mezokövesd girls are wont to be, but she wore a dozen petticoats

under her skirt, all the same, just to show that she was anything but penniless

; also, to prove this fact, there was her bedding. It was piled on a cart and

taken to the new home, where her fiancé's female relations had the duty-or the

privilege?-of unpacking it.

Criticism would have been far from tolerant, had there been any occasion for

it, but Juliska's trousseau was impeccable. Accordingly, her mother-in-law gave

her the grandest wedding cake that I have ever seen-a splendid affair, hung

all over with ginger-bread hearts, and swords, and hussars, and babies-especially

babies. Two girls carried it up to the bride's house on a stretcher.

The guests arrived with gifts of wedding cakes of their own. These had the

shape of churches, stags, and hens outlined in candy; but the reason why these

shapes were traditionally repeated remained a mystery. They had always been

so. finally, one little girl presented Juliska's parents with a big rag doll,

whether as a substitute for the daughter they were about to give up or in anticipation

of a grandchild seemed doubtful.

The church ceremony was quite simple and soon over. Not so the dinner. When

we left, the first few courses had barely disappeared ; there had only been

hen soup, stuffed cabbage with homemade sausages, paprika chicken, roast duck

and geese, curd cakes, and pastry, so far. It was about to begin all over again

and finish up with fánk, a kind of glorified griddle cake, and sweet pastries,

the whole generously washed down with the slightly sour, light wine of the countryside.

We spent the night at Eger in an excellent hotel. The city has a Turkish minaret

and on a green hilltop the ruins of the castle which a Hungarian amazon, Katica

Dobó, with a little army of women, helped their weary and war-worn menfolk defend

against the Turk.

While Eger has a number of beautiful baroque houses, courtyards, and gates

dat

ing from the days of Maria Theresa, the city's finest building is the Catholic

seminary and library.

THE HORTOBÁGY PLAIN EXPLAINS DEBRECZEN'S PROSPERITY

János and István were looking forward to finding historical relics in Debreczen,

but they were disappointed. The War of Liberty in 1848-49 is the period that

fires the romantic imagination of every Hungarian boy. To Debreczen, the big

city in the heart of the great plain, fled the first independent Hungarian cabinet

when the Austrian army was bearing down upon Pest, bombarding the town from

the Buda Hills. In Debreczen's Big Church the dethronement of the Habsburgs

was declared 83 years ago, and here Kossuth was established Governor of Hungary.

János went to sleep that night over a volume of Petofi's revolutionary poems.

but when we climbed out of the eiderdown beds of the Golden Bu11 next morning

we found little to gratify our curiosity.

There is the Big Church, to be sure, the old college, the little old houses

in the market place, but when all is said and done Debreczen is just a vast

Hungarian village, a multiplication of endless village main streets, until you

come to the handsome new university buildings in the Nagyerdo, the city's forest

park.

With the memories of the wedding feast still vividly present, we spent little

time over lunch and made an early start for Hortobágy in a hired carriage and

pair.

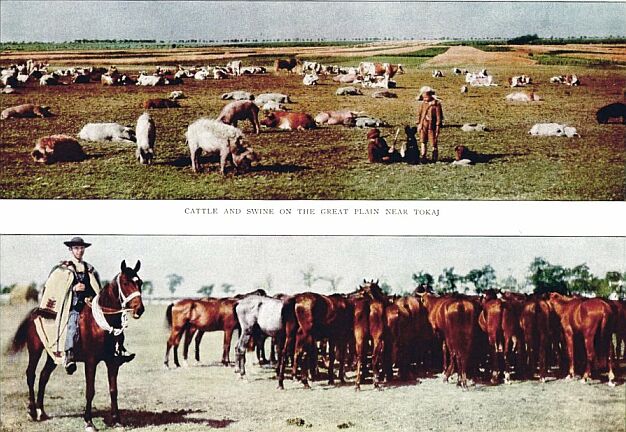

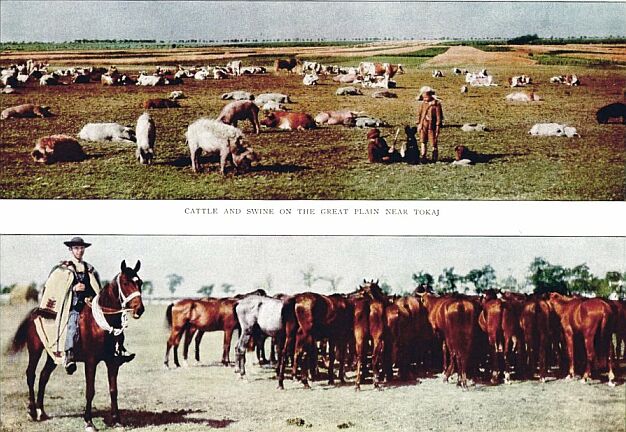

Hortobágy is really what Debreczen stands for and lives on-a vast puszta that

belongs to the city, an unbroken area of pasture land, where the city's famous

cattle and horses are bred. It was what tempted the nomadic Asian race of Magyars

to stay in the fertile valleys of the Duna (Danube) and Tisza rivers when they

came across the Carpathians in search of fresh pastures a thousand years ago.

HERDMEN OF HUNGARY LIVE IN HUTS OF CLAY AND REED

We spent the night at an old inn, the only stone building far and wide, on

Hortobágy. Cattle ranchers and horseherds live in reed and clay huts, alone

with the sun, the stars, with infinity and their animals. (See "Hungary,

a band of Shepherd Kings," by C. Townley-Pullam, in the NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

MAGAZINE for October, 1914.)

When I came out in the morning, István was trying to make friends with an old

cowherd who was having a little morning drink by himself in front of the inn.

"Aren't you warm in that sheepskin cloak, uncle ?"

The Hortobágy herdsman is very taciturn by nature, but then István is irresistible.

"It keeps me cool, son ; keeps the sun off."

"Then what do you wear in winter ?" "This same cloak. Keeps

the cold off." "Have you ever been to Budapest, uncle ?"

"I have, in 1896, when they had that exhibition on."

"Not since ? I wasn't born then. But of course you go into Debreczen often

?"

"What should I go into Debreczen for, son ?"

"Oh, just to see the town and the people and buy things in the shops-go

to the movies..."

All the contempt of the puszta dweller for the scurrying busybodies in the

city lurked in the old man's smile as he sat there, unchanging, unmoved as Hortobágy

itself.

"I haven't been in Debreczen these ten years ; the women go in and get

what we need."

What he needs is bacon, paprika, and tobacco-and a pair of boots every ten

years or so. The sheepskin cloak lasts a lifetime.

HORTOBÁGY CATTLE ARE BRED IN THE OPEN

It took some time, but István got him round his little finger at last. He did

it by singing the praises of the cows in Dombori. Our Hortobágy cowherd wouldn't

stand for that. He has a pride of his own. He wanted to show us that 'I'ransdanubian

cattle were just miserable cats as compared to those on Hortobágy. And he began

to show off. He just stood by and watched us-a man who is sure of himself. The

cattle didn't belong to him, but he belonged to them-more than to the world

of human beings in the city.

Some of the best cattle in Europe graze on the Hortobágy plain, hardy from

being bred in the open air summer and winter, and some of the finest horses

in the world can he found in the city of Debreczen's famous stud.

Of course János wanted to ride bareback. In consequence I hurried over the

preparations for departure.

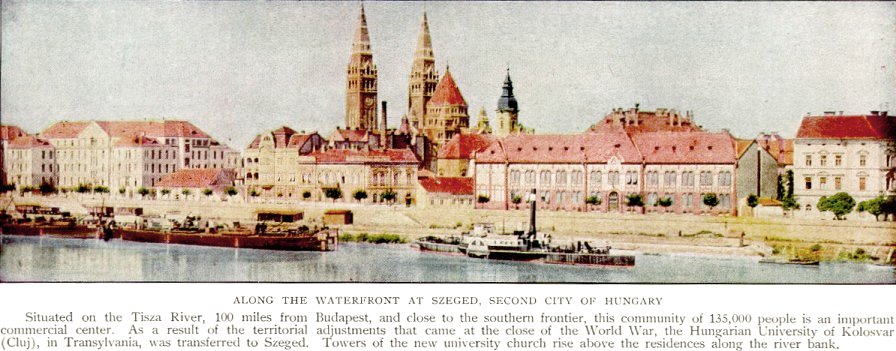

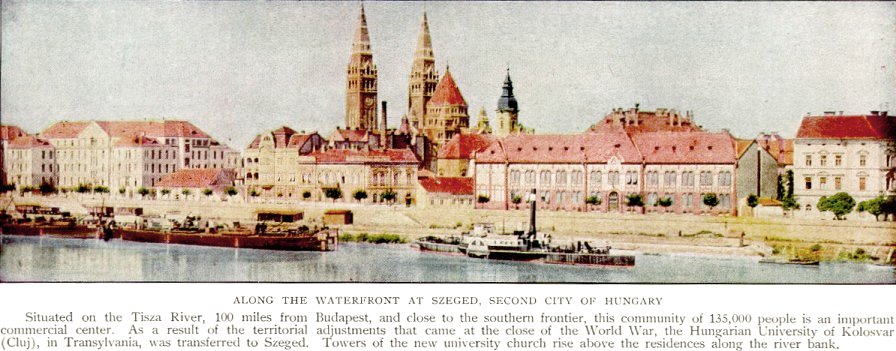

"But we have really seen nothing of Hungary," my sons complained.

"The cities-Pécs, Kecskemét, Szeged-the Tisza River, grape-picking at Tokaj-there's

so much more to be seen."

I mentioned school, about to begin. János retorted with something about the

advantages of learning history and geography in the practical way.

Finally a telegram from home set an end to the discussion. It ran

"Carpenters departed ; fall cleaning completed; cook returned; paprika

preserves in full swing. Longing for my family."

There was no resisting such a summons. The next day saw us on our way home,

to tell about our experiences and to discuss what would be the best thing to

do next summer.

HUNGARY

has been without a king since the Habsburg family was dispossessed in 1918.

But the country that never cared for the Habsburgs has suddenly turned loyal,

more loyal indeed than Austria, which had her emperors to thank for her wealth

and luxury.* Hungary still calls herself a kingdom and has constitutionally

remained one.

HUNGARY

has been without a king since the Habsburg family was dispossessed in 1918.

But the country that never cared for the Habsburgs has suddenly turned loyal,

more loyal indeed than Austria, which had her emperors to thank for her wealth

and luxury.* Hungary still calls herself a kingdom and has constitutionally

remained one.